“Think like a hacker” is an adage that works like a golden pill in the world of cybersecurity. Indeed, staying ahead of online hackers requires involving a smart ethical hacker on your team.

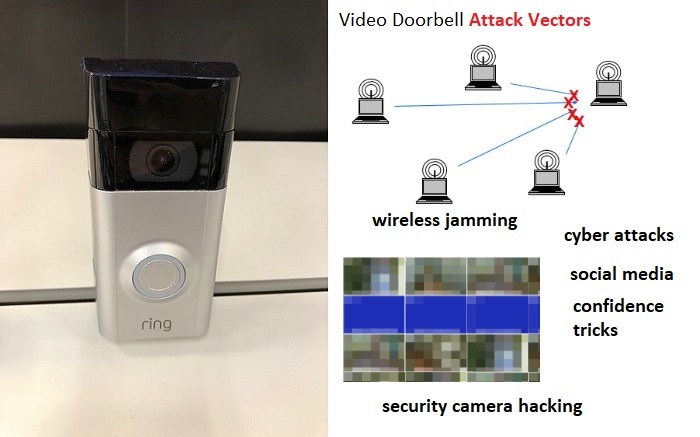

Testing for vulnerabilities in IoT devices is a bit more difficult. It is beyond the user to be able to trace the precise attack source. The threats can spring from anywhere: smart meters, edge devices, field routers, people, objects, network systems and connectivity protocols.

The biggest vulnerability in branded IoT devices is that the user simply has no means to plug their own security holes. While an Internet attack may depend on user actions such as opening a malicious link or falling for a confidence trick, with IoT security breaches, it makes no difference whether or not the user was careless.

It can be as simple as someone hacking a security camera and making you believe that they will kidnap someone ot miscreants faking out AI to confuse the driving path of an autonomous vehicle leading to accidents.

Testing Branded IoT Devices for Security Breaches

As discussed in the previous section, if you’re a consumer, your options in doing penetration tests for your own IoT device are quite limited.

However, you can always test for some basic security loopholes such as “shipped passwords.” If the default shipped password is some combination of “12345678,”, then you must assume the device has already been compromised.

If the password is slightly more decent, you need to use some proxies, password crackers or sniffers to hack your device. Towards this end, if the brute penetration is not yielding any results, then you’re safe.

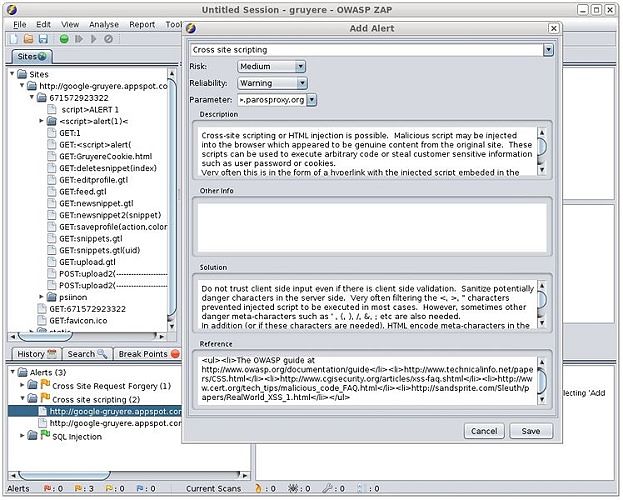

If your IoT device operates through a web dashboard, then you should check the security status using a free tool, OWASP Zed Attack Proxy. If there are no web attack vectors such as cross-scripting or SQL injections, then you have plugged a major security hole.

With IoT devices, there are additional attack vectors in the cloud, mobile apps and those that are due to data privacy requirements. There is not much you can do about them apart from monitoring security updates from the manufacturer and app company.

IoT Penetration Testing in DIY Projects

If you’re working on your own DIY projects in IoT, penetration testing is doable on your own. Wireshark is a popular tool used for penetration testing in DIY projects.

First, you have to map the attack surface areas and main vulnerabilities that will affect the device.

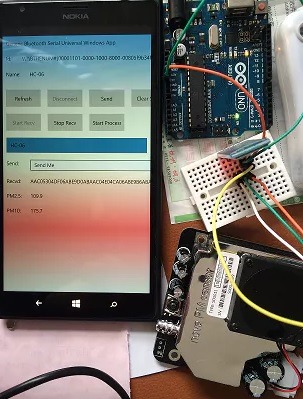

You need to understand the trust relationship between components which have connectivity. Let’s take the example of the Air Quality Monitoring System Project in the above link. From a security viewpoint, the vulnerable components are:

- HC-06 Bluetooth module: subject to denial of service, eavesdropping, and malware attacks on Bluetooth.

- Smartphone: since the IoT device operates on a smartphone, it is subject to Bluetooth vulnerabilities that can hack a phone.

- Arduino board: the vulnerable components are USB ports. Through a bad USB, attackers can reprogram the ATmega328 micro-controller.

Once the micro-controller is compromised, your machine is vulnerable to hacker manipulation. Thus, we must map the most vulnerable components of an IoT project and study the relationship between them.

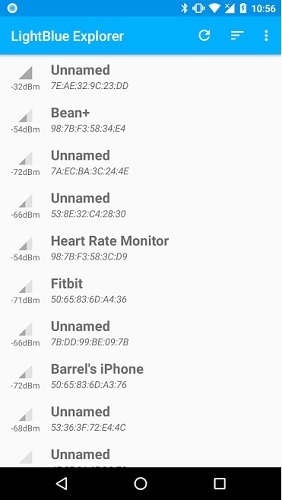

In this case Bluetooth is the most common threat, so you need to keep track of all the nearby Bluetooth connections. There are apps like LightBlue that allow you to get a bird’s eye view of Bluetooth devices in your network.

The next step is to use Wireshark or other penetration testing tools to check your device vulnerability for Bluetooth attack vectors and a bad USB. For this you need to first reset the device to an insecure stage.

In Summary

Although branded IoT devices are vulnerable to possible manipulation by external agencies, it is not always a cause for alarm. Many device makers are still in a learning stage, and the security benchmarks will improve with time.

Always insist on device encryption, and seal your Internet gateways with Wi-Fi 6 or WPA3 routers. They can help you deal with the uncertainties of many kinds of attack vectors.