Like most tech journalists, I have a graveyard of obsolete IoT devices. There are fitness trackers, earbuds, a drone, homemade connected clothing, smart home light switches, devices for retrofits, and pet toys, to name a few. Overall, at least 95 percent of these products fell victim to planned obsolescence, or the company went bust or withdrew from the product from service. The rest suffer from an absence of “right to repair” options.

The problem of device obsolescence in IoT

While the choice to no longer use a smart device may be the owner’s choice, there’s another problem when it comes to IoT – device obsolescence. A company goes bust or is acquired. It stops supporting older devices or updating the device’s software. A security problem forces the device out of operation. Or technology standards evolve faster than the IoT device.

When it comes to IoT, useless devices are a significant problem. The ubiquity of connected devices means that many of us own products that are embedded with IoT whether we choose this or not. These include many big-box products, such as washing machines, refrigerators, and kitchen equipment, which traditionally have an average lifespan of over a decade.

But their functionality is gone when the software is no longer updated. We’ve seen it happen with thermostats, smart bulbs, smart home hubs, speakers, and smart home security. That leaves many unhappy consumers who’ve contributed to the problem of significant electronic waste (e-waste) with devices they can no longer use, which contain components that they cannot easily recycle. Their only option is to invest in newer devices, and thus, the cycle continues.

What are the laws around planned obsolescence?

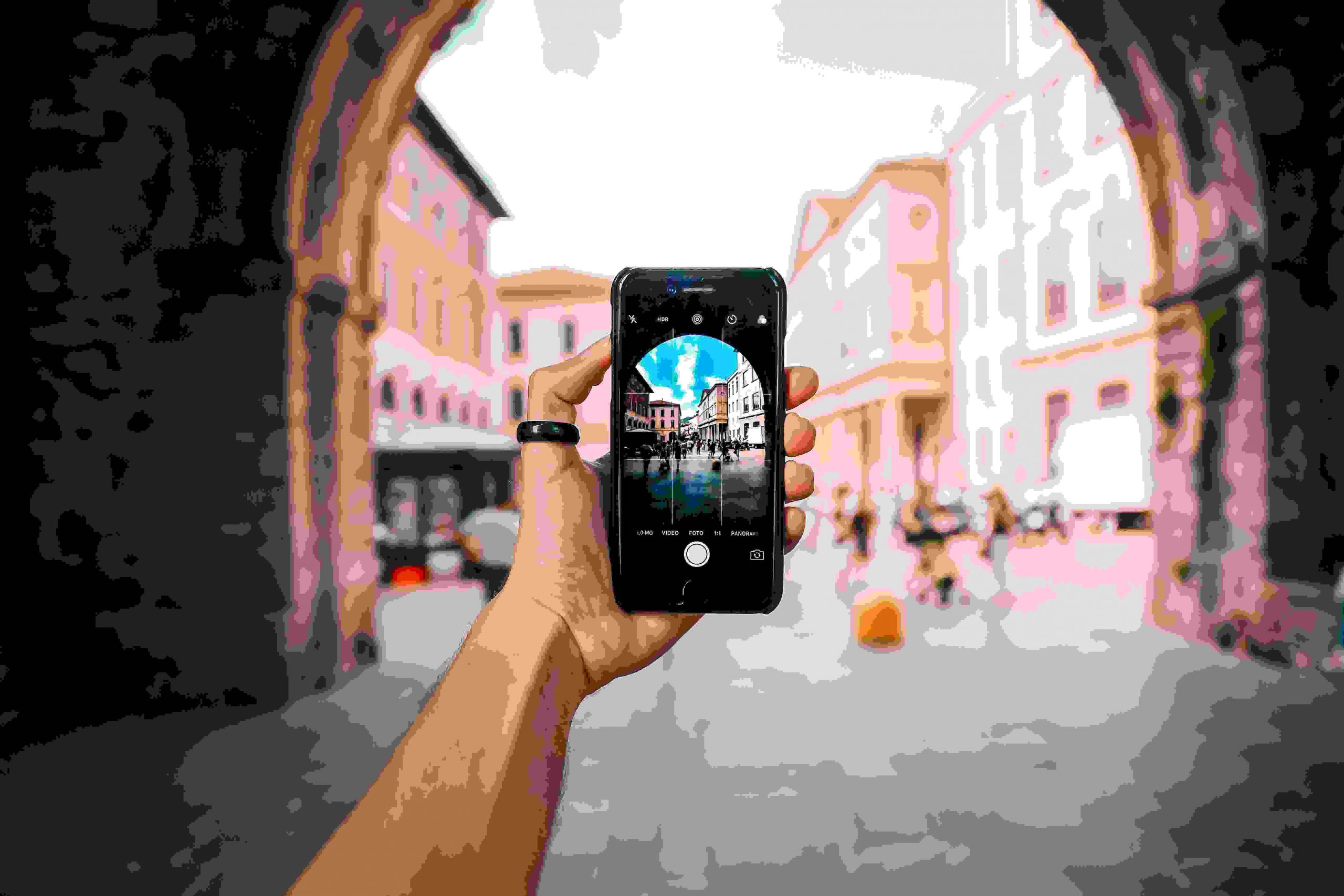

So far, the litmus test for obsolescence has been iPhones. Earlier this month, Marketeer reported that Apple faces a new lawsuit from Portuguese privacy consumer organizer Deco Proteste. The lawsuit alleges that Apple has programmed the iPhones 6, Plus, 6S, and 6S Plus to become obsolete, forcing consumers to invest in new equipment earlier than expected.

France was the first country in the world to ban unfair planned obsolescence in 2015. It’s punishable by two years of imprisonment, €300,000 fine, and up to 5 percent of a company’s annual average turnover. Last year, following an investigation by the Directorate-General for Competition, the Apple group agreed to pay a fine of €25M following an investigation which began in 2018. According to a press release by the DGCCRF:

“The DGCCRF has shown that iPhone owners were not informed that the updates of the iOS operating system (10.2.1 and 11.2) they installed were likely to slow down the operation of their device. These updates, released during 2017, included a dynamic power management device which, under certain conditions and especially when the batteries were old, could slow down the functioning of the iPhone 6, SE models, and 7.”

A complaint from Altroconsumo (an Italian consumer body ) also led the Administrative Court of Rome to order Apple to pay a fine of 10 million euros.

So much for subscription as a service

Companies promise software updates and security patches to keep our smart home devices operational and secure, but what happens when the product is shuttered before its lifespan?

In 2019, Internet provider Spectrum shuttered its home security service, leaving customers who bought locked-down custom firmware Zigbee-based hardware out of luck. The devices are not only bricked but worse. Spectrum reportedly firmware-coded its devices to be incompatible with other devices. If you own an original Samsung SmartThings hub from 2013 or a SmartThings Link for NVIDIA® SHIELD™, your hardware will stop working on June 30 of this year.

What should we expect as consumers when it comes to device obsolescence? On the one hand, we’re promised software as a service with over-the-air updates to our connected devices by building a relationship between consumers and retailers for a foreseeable period of more than a decade. Consumers should reasonably expect their security service to last more than six years and their hub to last longer than seven years. Or should they?

The open-source solution

Smartwatch pioneer Pebble closed its doors in December 2016, with Fitbit acquiring some of its assets, including key personnel, for a disclosed amount of somewhere between 23 million and 40million. The company was one of the trailblazers in connected watches, selling over two million devices since its launch in 2012. The company raised over $10 million in funding on Kickstarter.

Fitbit ended its support for Pebble watches in 2018. This meant Pebble owners no longer had access to software updates, replacement chargers, or warranty service.

However, Pebble has a vibrant developer community. They’ve published over 15,000 watch faces and watch apps and 130 companion apps, libraries, and packages. Developers performed over 4.6 million builds on CloudPebble. After Fitbit, Pebble morphed into the unofficial spearhead organization to advance the Pebble platform via the Pebble developer community. The community funds grants, hosts competitions and “maintain and advance Pebble functionality in the absence of Pebble Technology Corp.”

Planned obsolescence vs. leaving room for exponential innovation

We live in a time when technology is advancing at exponential rates – how long can we expect our devices to last before they become obsolete? Mainstream consumer IoT has been around for less than a decade. In that time, we’ve seen an explosion of innovation in adjacent technologies. These include 5G, Bluetooth, software, machine learning, data science, materials, and batteries. Shouldn’t we expect our products to evolve as technology advances? What is the balance?

Right to repair

In February, the European Commission published its Circular Economy Action Plan. The plan is to revise consumer law to ensure consumers know the product lifespan and repairability at the point of purchase. It also strengthens consumer protection against planned obsolescence and the right to repair. Planned regulations will ensure device design includes energy efficiency, reparability, upgradability, maintenance, reuse, and recycling. The regulations currently apply to washing machines, dishwashers, fridges, and displays (including TVs) across Europe.

The new laws will require producers to make most spare parts and repair manuals available to professional repairers only. This will be upheld for seven to 10 years after retiring the product from the market. Manufacturers must make the latest firmware, software, and security updates available to professional repairers as well as access to spare parts.

However, according to Repair EU, there’s no specific requirement for manufacturers to continue updating software throughout a product’s lifetime. This means that a manufacturer could comply with the regulations while not committing to support products with software or security updates for their products’ entire lifetime.

We call it repairs; manufacturers call it illegal tampering

Companies such as Apple void warranties where consumers have repaired products by stores outside of their approved circle. Worse, those without the right to fix their own tractor or connected car can be accused of illegal tampering.

A single combine harvester contains over 125 software-connected sensors in a single combine harvester. Each sensor connects to a controller network. A problem with any one of those controller networks will require diagnostic tools not available to farmers, sending them back to the dealer for a repair.

According to agricultural equipment experts, these sensors and their associated controller networks are now the highest points of failure on the product. Missouri farmer Jared Wilson lost thousands of dollars in income one season, waiting 32 days for his dealer to repair a mechanical valve on his fertilizer spreader. He believes that with the necessary parts and diagnostic tools, he would have performed the work himself.

In September 2018, the Equipment Dealers Association signed an agreement with John Deere. They agreed to make repair tools, software guides, and diagnostic equipment available to farmers from January 1, 2021. Farmers have long criticized the software lockouts backed into John Deere tractors. They lobbied hard and bills were introduced in over 32 states.

However, research by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group reveals that farmers are still waiting for access. Posing as a customer, a member of US PIRG called 12 John Deere dealerships in six states. Eleven stated they don’t sell diagnostic software. The other directed him to an email address from which he never heard anything back. So it’s fair to say that progress is slow.

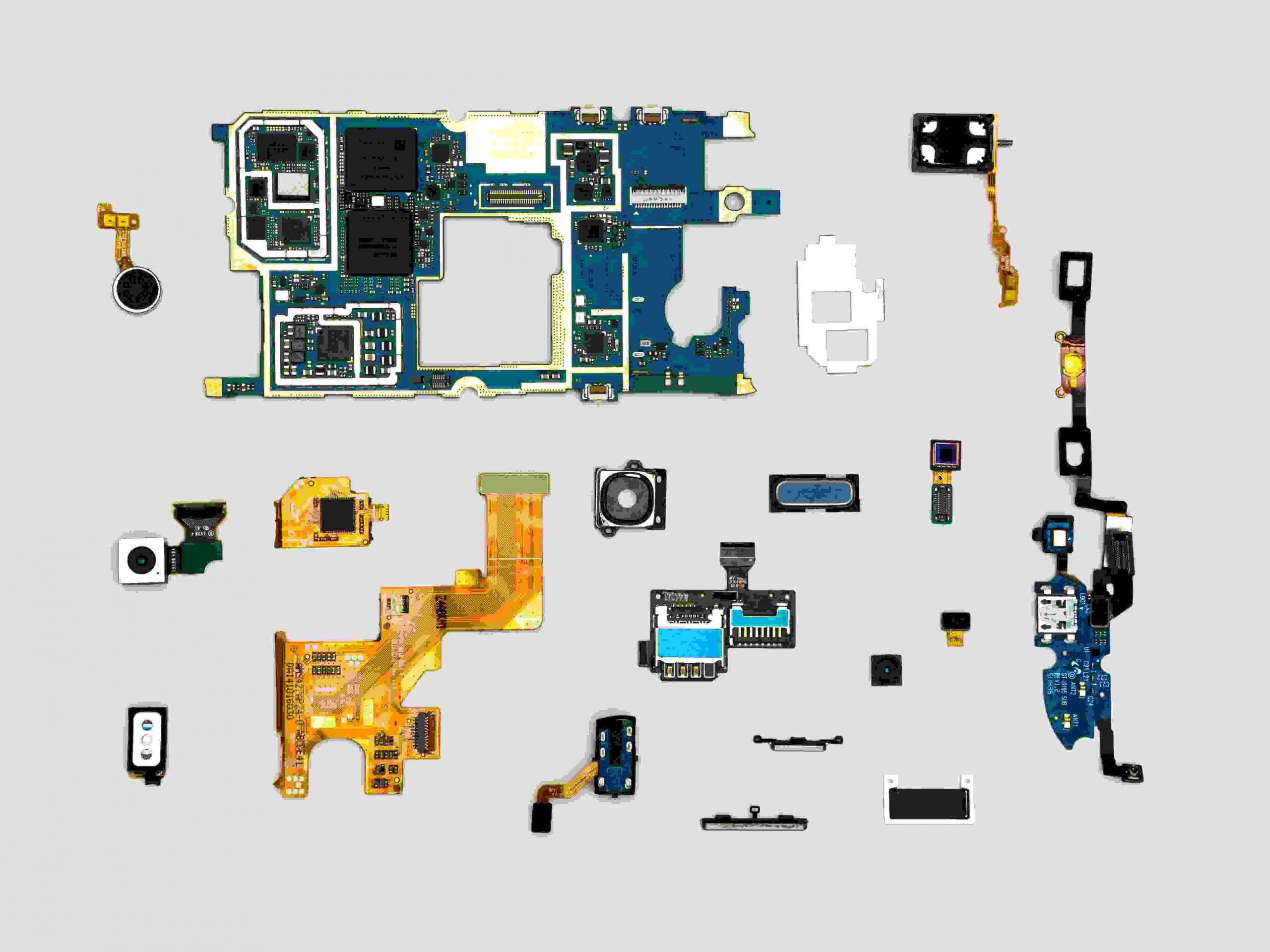

The solution starts in the design phase

We need modular, replaceable parts in devices. Use repurposed and recycled materials. But modular is hard. We’ve seen less than successful attempts at modular mobile phones and laptops. Consumer products should be designed to physically work in some fashion even if the software and app are defunct. This makes reuse possible even if all of the digital features are not operational.

We also need repairable products that don’t require postage to their country of origin for service. Prioritize the right to repair. Take connected cars. People have been tinkering with cars since their inception. There are plenty of amateur mechanics who want to understand what their cars can do and could do with modifications to their hardware or code. These issues are not going away, and manufacturers have an opportunity to really cement those relationships with consumers.