Robots on assembly lines are commonplace today. Many fear that the introduction of robotics will reduce employment prospects for humans, while others just fear robots in general.

While manufacturers hope to make human workers more comfortable with robots, the entertainment industry continues to convey robots as a threatening, potentially world-destroying army. A few recent experiments have revealed that fear of robots in the workplace might not be such a bad idea.

Factory designers expect the purchase of robots to increase productivity simply because they can perform repetitive tasks more accurately, and apparently faster than humans can. Modern industrial robots tend to be in the form of arms and look more like machinery than people.

In Step with the Robots

A study managed by Tokai University in Japan has raised some interesting ideas about how robot design can not only increase output through the input of the robots but can also inspire humans to work faster and more accurately.

The 2018 study hoped to see whether humans working alongside robots would experience what is known as “motor contagion.” This means that the human would simply start to work in sync with the robot, emulating its pace. Such a phenomenon is known to occur among human co-workers.

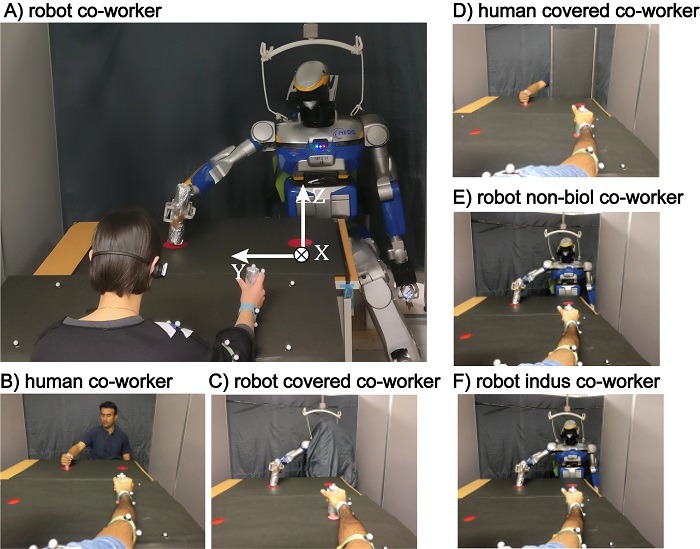

The study placed a human in front of a robot, with both expected to perform the same repetitive task. The robot appeared as just an arm in some sessions, but as a full humanoid robot in other sessions.

The results showed that the human co-workers did increase pace in line with the robot but only when the robot was shown in humanoid form. The human workers weren’t inclined to keep up with the robot when it looked more like a piece of machinery.

Although the study found an increase in human task frequency alongside the humanoid robot, the accuracy of task performance didn’t increase in pace – meaning people worked faster but made more mistakes. Humans seemed to be keen to keep up with a robot’s movements and were prepared to sacrifice the quality of their results in order to achieve that.

Robot Supervision

A new study undertaken at the Université Clermont Auvergne in France for the American Association of the Advancement of Science advances our understanding of how humanoid robots influence human performance.

The results of this experiment were produced by Nicolas Spatola in the paper “Not as bad as it seems: when the presence of a threatening humanoid robot improves human performance.”

In this study, human subjects were required to apply intelligence to a repeated task. The task is known as a Stroop test. The subject has to identify the color of a word and not the meaning of the word itself. So if the word “blue” appeared in green, the correct answer would be green.

In previous usage of the Stoop tests, it has been discovered that the presence of others in the room performing the same test increases anxiety in test subjects, which in turn, impairs their accuracy. Even having someone in the room observing can reduce the performance of the test subject.

In this experiment test subjects were required to complete a cycle of Stroop tests unsupervised. The group was split into three. Group 1 performed the test again unsupervised. Group 2 was introduced to a robot that was warm and gave then positive messages and then watched as the test subjects performed the Stroop task again. Group 3 was introduced to an aggressive, insulting robot, which then watched as the subjects performed their second round of the test.

The angry robot can be seen berating a young French woman in the headline of this article.

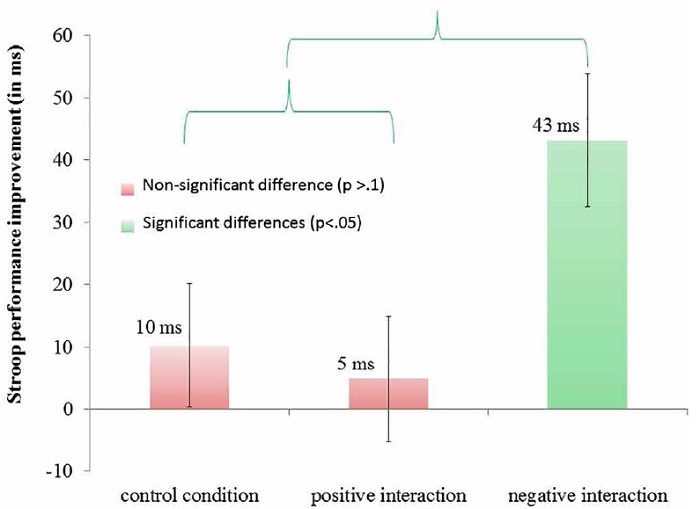

The results were astounding. The control group that had no robot present in the second round performed similarly to their first round. The group that was being supervised by the nice robot showed significant performance impairment. This was similar to previous uses of the Stoop test that found that a human supervisor reduced performance in the test subject.

The angry robot’s supervision more than quadrupled human productivity.

This experiment expanded previous knowledge that task supervision reduces productivity. It also showed that people tend to regard nice robots as equal to humans in that their awareness of the robot’s presence made their performance deteriorate. The angry robot, although it may have caused resentment, does not seem to have caused performance-reducing stress.

This experiment points to ways that humanoid robots can increase productivity without replacing humans.